How I Overcame Panic Attacks

You never forget your first panic attack.

I was 32. I was living in a brownstone on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. I’d just gone through a breakup. One minute I was fine; the next minute my heart felt like it was beating out of my chest. I had to lie down. I felt like I couldn’t control my breathing. It was terrifying.

My friend took me to the ER. The nurse took an EKG and gave me an Ativan. Within 15 minutes my heart rate had returned to normal.

Thus began a long struggle with panic disorder. My doctor gave me a prescription for benzodiazepines, aka benzos: Ativan, Klonopin. I began using them regularly.

The meds were supposed to help. But they only seemed to make things worse. When I didn’t take them, I went through withdrawal.

I had panic attacks on planes, trains, Ubers. Movie theaters. In a conference room for an important work meeting.

What does a panic attack feel like? I’d tell people: It’s like you’re being chased by a bear in the woods, and your pants are on fire, and giant hands are squeezing your chest like a vise and you’re about to have a massive heart attack. Other than that it’s quite pleasant.

I began to avoid situations that might be triggers for a panic attack. I avoided long car trips. I stayed away from gatherings in confined spaces. I relied on alcohol and pills to calm my nerves, in a never-ending cycle of dependence.

I realized: Panic disorder was ruining my life.

It wasn’t until I quit the meds—weaning myself off gradually—and started making lifestyle changes that the panic attacks subsided.

In this piece I’ll share what worked for me, and what I learned about the science of anxiety and panic attacks.

[Disclaimer: This is based solely on my personal experience and research; nothing herein should be construed as medical advice. Please consult your doctor if you are experiencing issues with panic and anxiety.]

Benzo Nation

The main treatment options for panic disorder are psychotherapy and medications. SSRI antidepressants like Paxil or Zoloft are typically recommended as the first choice of medications to treat panic disorder. SSRIs are not used to treat panic attacks, but rather to treat the underlying disorder that causes panic attacks. Psychiatrists may prescribe benzodiazepines, like Xanax and Klonopin, which are sedatives that act as central nervous system depressants.

The key difference between these two drug classes: SSRIs work more slowly and are used to treat depressive and anxiety disorders long-term. Benzodiazepines are fast-acting and well-tolerated with fewer adverse events, but their long-term use has major safety concerns due to their withdrawal and dependence potential.

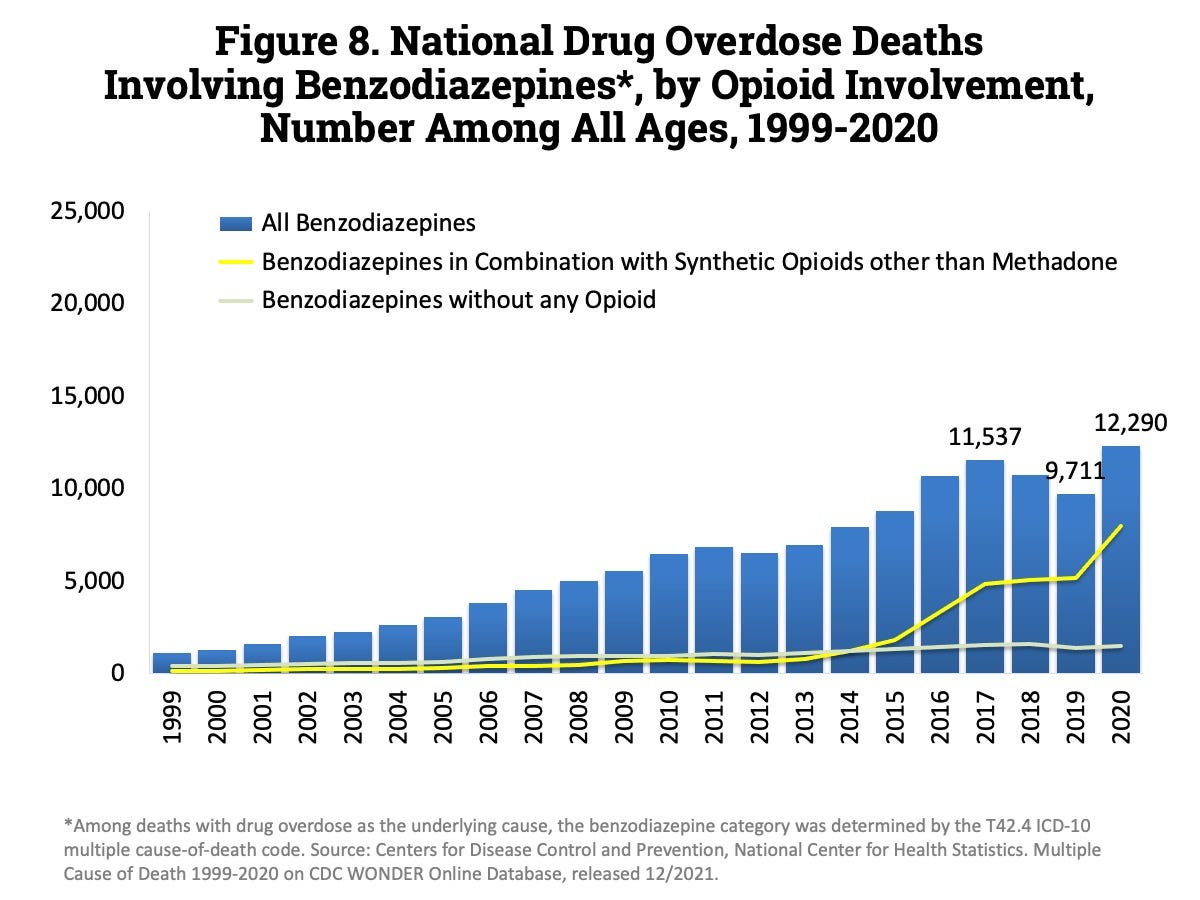

More people than ever today are using, and abusing, benzodiazepines. Over 30 million Americans reported past-year benzodiazepine use while 5.3 million reported benzo misuse. In 1999, there were 1,135 benzodiazepine-related deaths, and in 2017 that number hit 11,537. Benzos are particularly dangerous when combined with opioids.

Benzos have a high addiction risk. Studies have shown that up to 60% of people who are given a benzodiazepine prescription become long-term users.

College students are abusing benzodiazepine; rates of abuse have risen by over 400% in recent years. Students turn to drugs like Xanax and Klonopin to help deal with pre-test nervousness, heartbreak and overall stress. These medications are highly addictive, and those who abuse them can develop a deep dependence.

Scott Stossel wrote about this cycle in his book “My Age of Anxiety”:

“Many nights I would begin the evening fueled by caffeine and nicotine, which I needed to propel me out of torpor and hopelessness—only to overshoot into quaking, quivering anxiety. Thoughts racing, hand shaking, I would end the evening taking a Klonopin and then perhaps a Xanax and drinking a Scotch (and then another and another) to settle down. This is not healthy.”

The Neuroscience of Stress and Anxiety

Why are depression and anxiety at record highs in today’s America?

Psychiatrists see anxiety as a reaction to the stress and uncertainty of modern life.

A stress response is biologically designed to reallocate energy for survival. Stress starts when you perceive a threat—either something in your immediate environment, or a thought about the past, present or future. That signal is then relayed to your body, and your adrenal gland releases hormones: Epinephrine and cortisol into the bloodstream.

Cortisol’s main job is to boost your blood sugar, and epinephrine’s main job is to jack up your blood pressure, so you have fuel and a delivery method to sustain your muscles and brain in dealing with a threat.

These ancient fight-or-flight responses were designed to help us survive in the wilderness. Humans today have so rapidly out-evolved the requirements of those processes they are almost like an evolutionary throwback.

When we check Facebook and see a picture of our ex with a new partner, our brain still carries out that same biological fight-or-flight response, even though it has zero survival value for us now.

We evolved the stress response for a very particular reason. It’s helpful if you need to run away from a lion, or attack an enemy. In that moment we need to amp up our stress response so we can run faster, activate our muscle strength, think more sharply. But 30 minutes later, we should revert to our normal, relaxed state; everything should come back down to normal.

Modern society has created an epidemic of anxiety. Many of us are living in fight-or-flight mode all the time, and only occasionally do we go into relaxation mode.

How can we find better ways to cope?

What worked for me

I realized I had to stop relying on benzodiazepenes. It wasn’t easy. There were withdrawal symptoms. It took me weeks to wean myself off the medications, gradually.

Over time, I discovered non-pharmacological ways to manage panic attacks and stay calm.

I was able to control my stress response with simple lifestyle changes: Reducing my sugar and caffeine intake. Reducing alcohol consumption. Sticking to a regular sleep schedule. Getting daily exercise and sunlight exposure. Eating a healthy diet.

These changes worked. I haven’t had a panic attack in years.

I learned ways to calm myself naturally, without medication, when I felt the onset of panic: Breathing, cold exposure, yoga and meditation.

[Note: This is what worked for me; I am not recommending that anyone discontinue use of prescription drugs that may be helpful for them.]

Breathing

Slow, deep breathing helps to turn off the fight-or-flight response. Our breath regulates the areas of the brain that control autonomic arousal and stress. This is bidirectional: Breathing can control the stress response, and vice versa. Longer exhales tend to lead to more relaxation response and reduction in stress, while inhale-focused breathing tends to increase stress and make us more alert.

Exhale-emphasized breathing, with longer exhales than inhales in a 2-to-1 ratio, tends to drive parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) dominance and quiet the sympathetic (fight-or-flight) nervous system. This kind of breathing helps you relax and calm down.

Cold exposure

Cold temperature exposure for as little as two to three minutes a day can change the way the body responds to anxiety triggers. Some believe cold exposure helps jolt your system out of the fight-or-flight response.

When I felt a panic attack coming on, I’d stick my head in a cold shower, or apply ice to my forehead. This generally helped me calm down.

Yoga and meditation

My psychiatrist had me do yoga poses when I felt myself having a panic attack. I was surprised by how effective it was. Yoga and meditation affect breathing and heart rate in powerful ways. Meditating for a short period of time can lead to a state change—you’re calmer, more relaxed.

As Dr. Andrew Huberman of Stanford School of Medicine explains, when done repeatedly, meditation can lead to a trait change via neuroplasticity such that the your tendency to have stress is lower. You’re less likely to have panic attacks. Meditation helps change people’s physiology and brains in a permanent way, for the better.

Breaking the cycle

Mental health experts suggest other ways to identify and manage potential triggers for panic attacks.

I spoke with Dr. Samuel Sharmat, a psychiatrist based in New York City. He said:

“Panic attacks are always thought of as a psychological process—starting in the brain and working their way out into the body. But the opposite holds true as well: a physical symptom—especially a subtle one—can trigger a panic reaction which then feeds back to the symptom making it worse and escalating into a full-blown panic attack. I’ve seen this with airway reactivity, cardiac sensitivity, migraine sensitivity, and even stomach sensitivity.

If you think about it this way, you can treat the trigger before the panic attack spins out of control. Inhalers for airway sensitivity, cardiac meds for cardiac sensitivity, migraine meds for migraine sensitivity, and anti-nausea/vomiting meds for stomach sensitivity can all work to break the cycle. The approach doesn’t work all of the time; but when it does, it means one less psychiatric medication in your pill case.”

Panic attacks are incredibly upsetting and uncomfortable to experience. I have sympathy for anyone who has struggled with this disorder. I wish I’d had better education when I was younger about the causes of panic disorder and treatment options.

I’d love to hear your thoughts. How do you cope with anxiety or panic attacks? What’s worked for you?

Thank you for reading this week’s edition of Vitamin Z.

Until next time,

If you liked this newsletter, share it with a friend and tell them to subscribe!