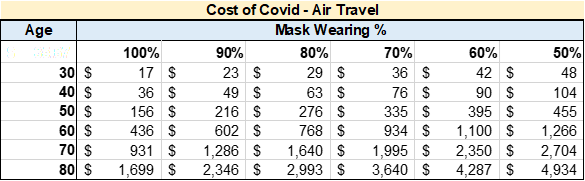

I calculated the health cost of flying. It's $36 for me. What is it for you?

A new model for weighing the health risks of air travel.

Hey all, greetings from Santa Monica!

This week I booked a flight to New York. I did what I always do before a flight: I built a personalized tool that calculates the health cost of flying through the lens of Covid-19 risk.

The calculation varies for each individual and flight:

For a 40-year old on a 5-hour flight with 100% of people wearing masks, the flight has a Covid cost of $36.

For a 65-year old on a 10-hour flight with 80% of people wearing masks, the flight has a Covid cost of $1,349.

Is It Safe to Fly?

In June I built a personalized Covid-19 decision support tool. The idea was to place a dollar value on everyday activities through the lens of Covid risk.

The response was amazing. My write-up was shared over 10,000 times. I got feedback from Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch and other health leaders.

Economic analysis can be useful for managing abstract risks. The Economist last week estimated that the economic value of wearing a face mask is $56.

With my New York trip coming up, I wanted to understand the risks of flying. I read every study I could find on airplane transmission risk.

I wondered: How can we use economic risk modeling tools to weigh the health risks of air travel?

How to Think about Air Travel

To understand the health risk of flying, we need to look at 3 factors:

Risk of exposure on a flight

Location risk / prevalence

Personal risk

On the plane

At first thought, being trapped in a metal tube with hundreds of strangers doesn’t sound too appealing right now. Yet experts say flying is relatively low-risk. Infectious disease doctor Lin Chen says the overall rate of infection from air travel is "very, very low."

How are planes ensuring safety?

Ventilation: Aircraft ventilation systems are very effective in eliminating airborne pathogens. The air in the cabin of a plane turns over every 2-3 minutes. Air is run through HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filters, the same things they use in hospitals. They filter out 99.97% of virus-sized particles.

Masks: Since airlines started requiring masks and telling sick people not to travel, there have been very few confirmed cases of coronavirus spread on airplanes. On a flight from China to Canada, a passenger with a symptomatic case of Covid-19 did not infect any of the 350 passengers on board.

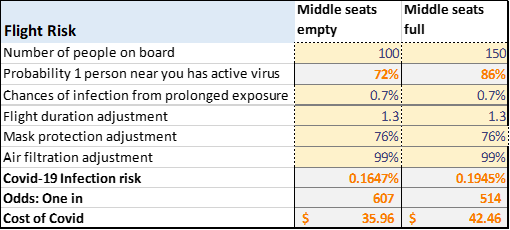

I read an analysis by M.I.T.’s Arnold Barnett, an expert in mathematical modeling who focuses on issues of health and safety. Barnett estimated the chance of contracting Covid-19 on a 2-hour domestic flight is one in 7,700. If all the coach seats are full, the chance is one in 4,300.

Barnett’s study doesn’t consider the risk of becoming infected during boarding and deplaning, moving about the cabin during flight, or how the odds might change with longer or shorter flights.

In my model, I added a few adjustments:

Number of people on board: A more crowded flight means greater chance of being exposed to someone with an active infection (especially if the middle seats are occupied).

Flight duration: Risk is higher for long-haul flights.

Location: Risk is lower for flights taken from parts of the globe with few cases.

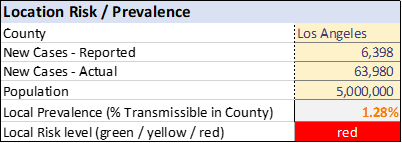

Location risk / prevalence

This determines the risk a random asymptomatic person in your area could expose you to the virus.

Experts say the 7-day moving average of new cases per 100,000 people is the best indicator of how many people in an area are transmissible. I multiplied the reported number of cases by 10 to estimate the actual number of new cases, per CDC guidance.

Personal Risk

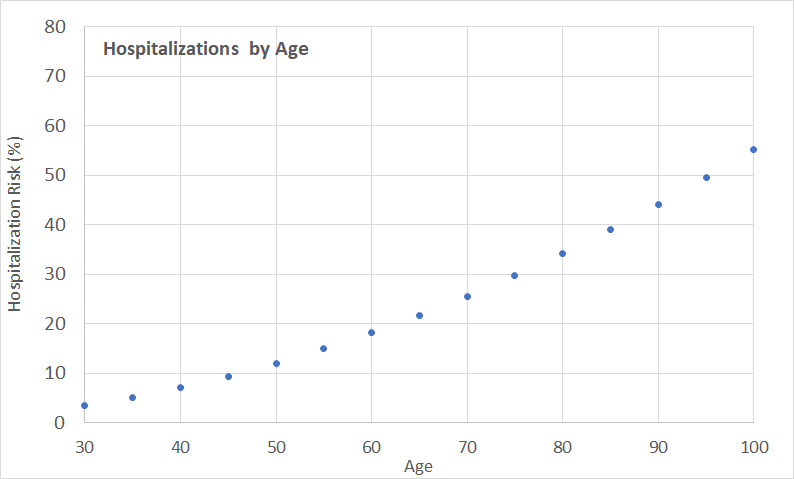

If I contract the virus, how likely am I to develop serious complications?

I did a regression analysis with data from over 100,000 confirmed cases in Florida. I derived a formula that lets you input a person’s age and estimate their chance of hospitalization and death.

For a 40-year old who contracts Covid-19, the model says there’s a 7% chance of hospitalization and a 0.3% chance of death. (Note: This is a high-level estimate and does not take into account blood type or comorbidities.)

Economic cost

With the coronavirus, there’s an implied health cost of everyday activities based on the risk of infection.

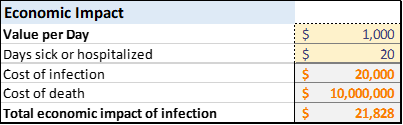

My model places a dollar value on the economic impact of a Covid infection. This varies by age and likelihood of developing severe complications. The estimate is based on:

The value per day of pain and suffering. How much would you pay per day to avoid being sick?

The economic cost of a human life. US federal agencies estimate the value of a statistical life (VSL) at $7-9 million.

Let’s say you’d pay $1,000 a day to avoid being sick. Then a disease that makes you seriously ill for 20 days would cause 20 * $1,000 = $20,000 of damage.

How can you apply dollars to an illness that can mean life-or-death? We need a good yardstick to help us make difficult decisions. Time and money are the best measuring sticks we’ve got.

Notes on Airport Risk

Risk level may vary by airline and airport. JetBlue has extended its open-middle-seat policy through October 15, and Delta is leaving adjacent seats open through January 6.

Air travel is unpredictable. People have shared images of crowded airport terminals where distancing is impossible. When it comes to air travel, or any kind of public transportation, you can’t eliminate all the risk.

How can we make flying safer?

Soon we’ll have rapid point of care antigen tests for anyone boarding a plane. They’ll tell within 15 minutes whether someone has the coronavirus, accurately and within first onset of symptoms or contagion. This should make flying safer.

Using Data for Better Decisions

This model is designed to help people assess the health economic cost of flying. I built the model so anyone can enter their own estimates. You can adjust the model for age, location, flight duration, and mask wearing. You can change the dollar value of a sick day.

My model does not account for:

The role of super-spreaders, which is still poorly understood but seems to be a major driver of virus transmission.

Risks of other parts of air travel (airport exposure, boarding / deboarding, impact on immune health).

The long-term effects of Covid-19, which may be serious in some cases and are still being investigated.

If you must travel, do so thoughtfully, safely and with deliberate attention to your own safety and the safety of others. And we can all collectively lower risk if we limit travel to times when we really feel we need to.

Important Disclaimers

The model is a marginal analysis at the level of each individual, but from what we know about disease, the collective costs are greater than the costs that individuals bear on the margin. If everyone made decisions based on this analysis, there is a risk that they would all be worse off than expected because they could drive up the spread.

The model is directional at best. It’s not meant to give you any definitive yes or no answers as to whether you should engage in any activity.

The model is a work in progress. The assumptions are not perfect. I’m sure many of you will have feedback. I welcome any and all comments.

My hope is that this tool will stimulate more rational, data-driven decision making when it comes to the coronavirus.

You can view the model here. Feel free to play around with it. Share it with others who may be interested. And please let me know what you think!

Until next week,

By Daniel Zahler

I’m Daniel, a healthcare and life sciences consultant based in Santa Monica, California. Every week I write an email newsletter with perspectives on health and wellness trends, and strategies & tactics on how to optimize cognitive, physical and emotional health.

Enjoy this?

There are a few things to do:

Hit the “like” button

Follow me on Twitter.

Become a subscriber!